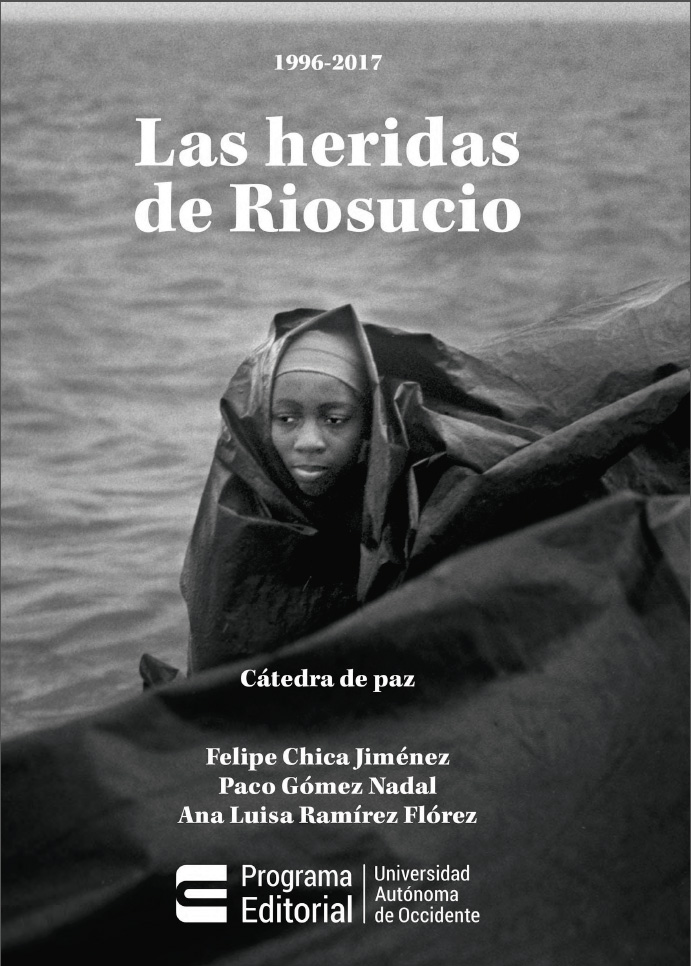

1996-2017 Las heridas de Riosucio / Felipe Chica Jiménez, Paco Gómez Nadal, Ana Luisa Ramírez Flórez, Paul Smith.– Primera edición.– Cali: Universidad Autónoma de Occidente, 2017. 70 páginas, fotografías. ISBN: 978-958-8994-35-2 1. Desplazamiento forzado – Riosucio, Chocó (Colombia). 2. Conflicto armado – Riosucio…

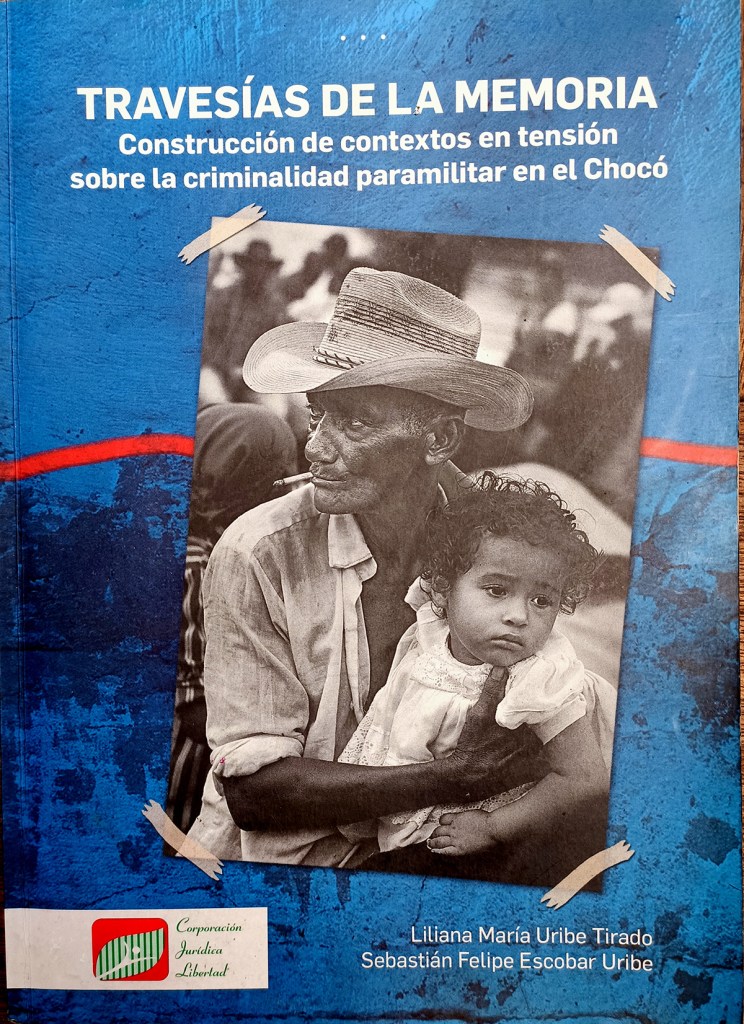

Travesias de La Memoria

Liliana María Uribe Tirado

Sebastián Felipe Escobar Uribe

Corporación Jurídica Libertad · Mayo 2017

ISBN: 978-958-57178-8-6

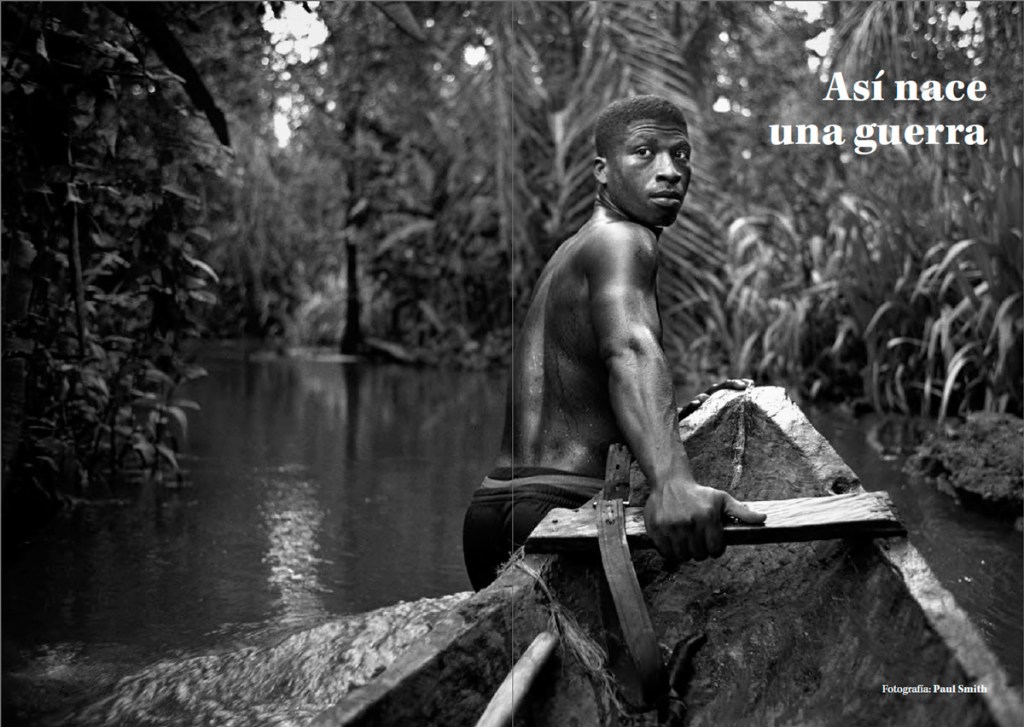

5 fotografías por Paul Mark Smith

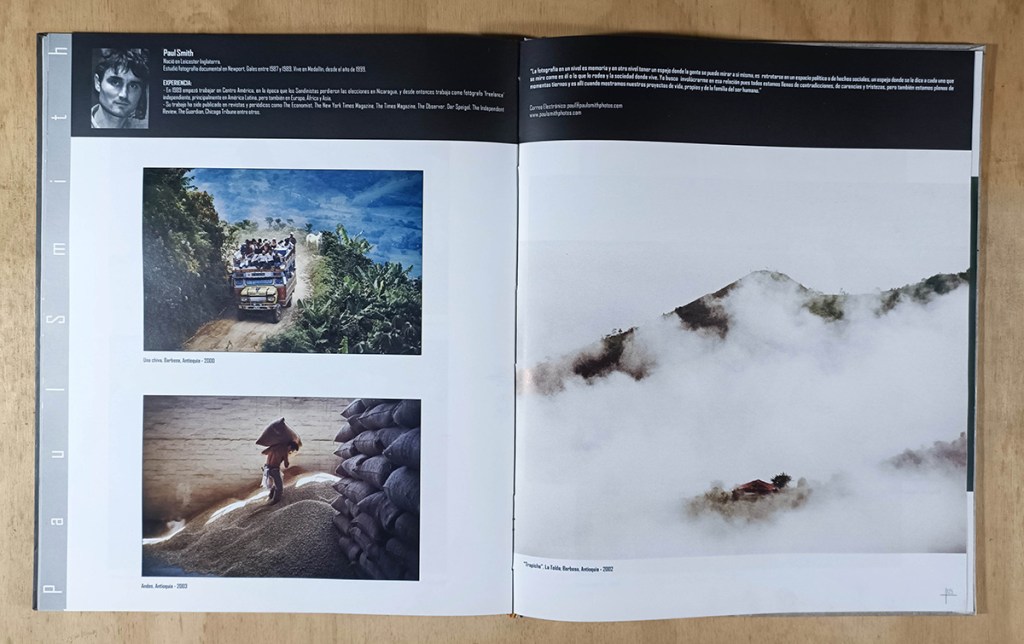

32 Reporteros Gráficos Antioqueños

ODEA/Gobernación de Antioquia · 2005 (?)

6 fotografías por Paul Mark Smith

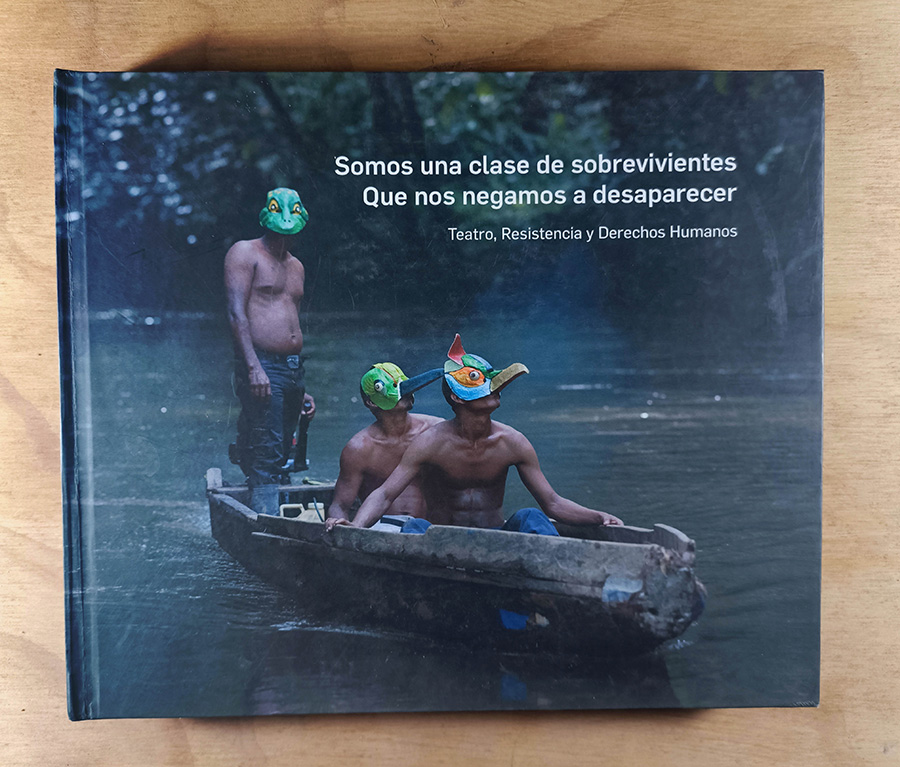

“Somos una Clase de Resistentes…” Teatro, Resistencia y Derechos Humanos.

ISBN: 978-958-57178-5-5. · Colombia 2015

Portada, 100+ fotografías y diseño por Paul Mark Smith · Proyecto colectivo

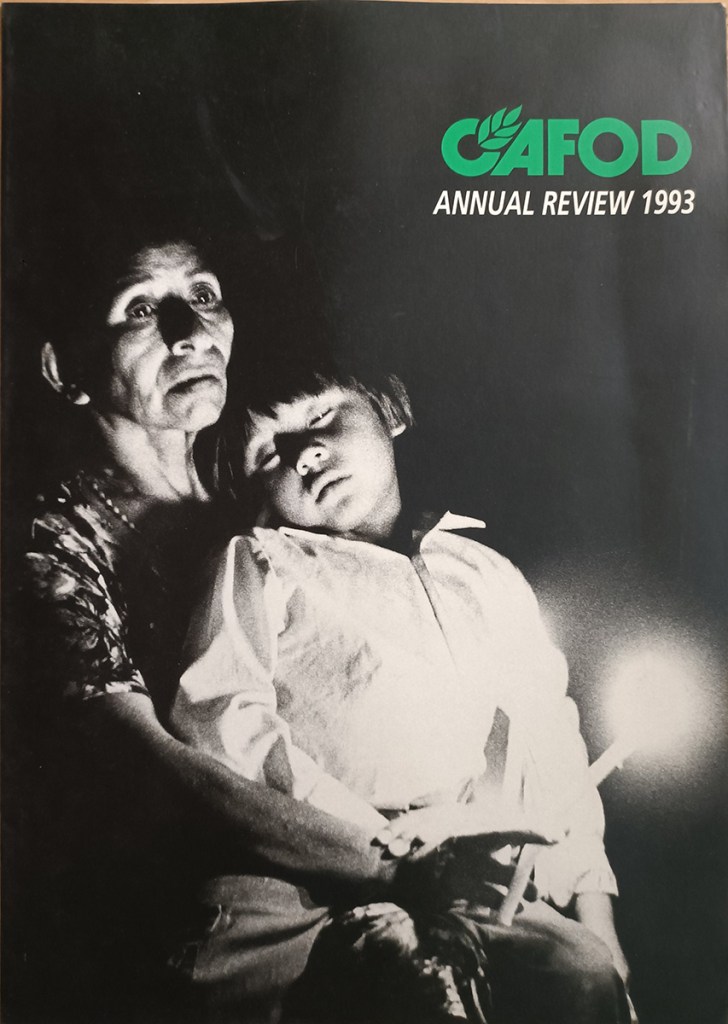

Agenda CAFOD 1996? · Fotografía: Diciembre de 1994, Barrio Diana Turbay, Bogotá

Semana Turismo· Julio 2018 – articúlo y fotografía

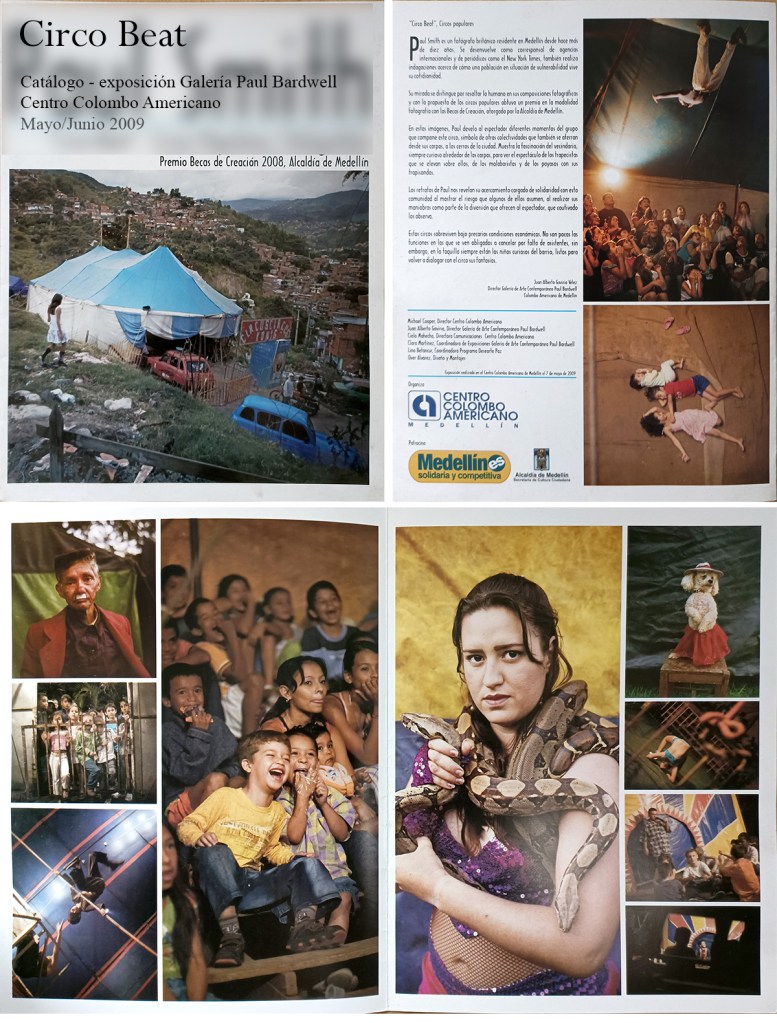

Circos Populares en la ciudad de Medellín · 2008 – 2009

Mozambique. Returning home as the civil war comes to an end · Times Educational Supplement, 1994

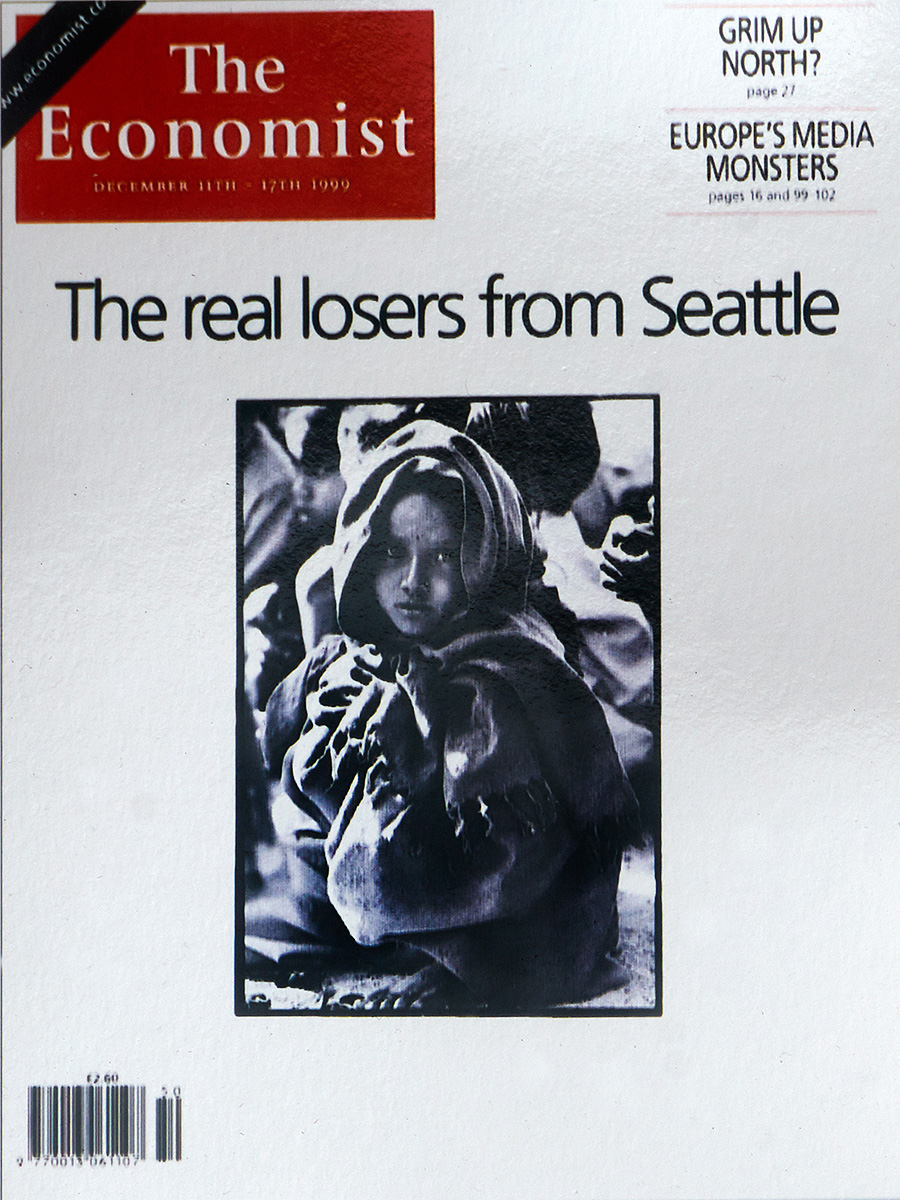

The Economist · 1999

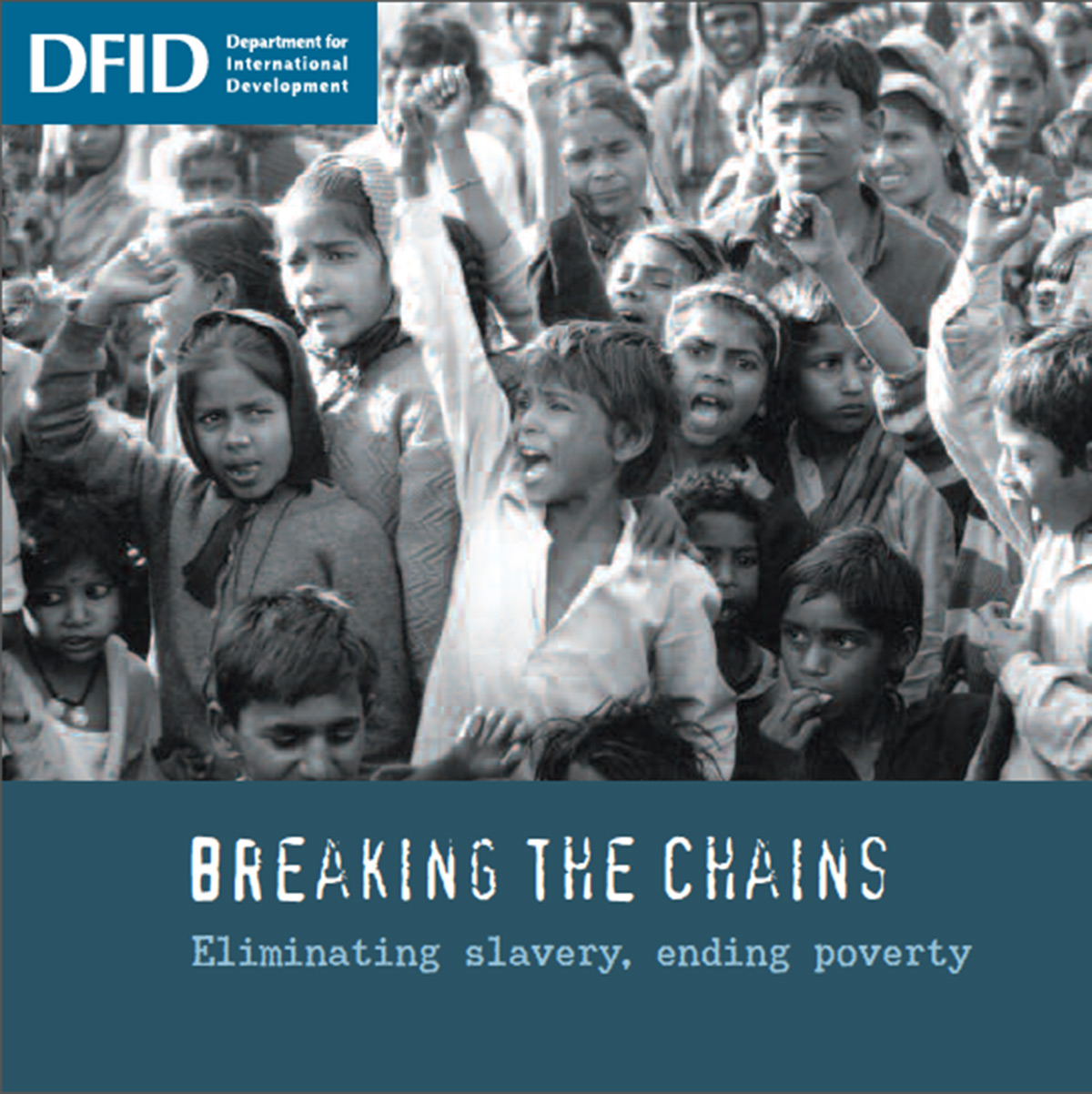

Below is the Economist editorial (9th December 1999), which refers to the cover image I took whilst with child workers – the children of bonded labourers – on the outskirts of Delhi. That an editorial should refer to an image is strange in itself (no so strange that the article is in defence of neoliberalism), but stranger still is the use of the full-frame photograph as I printed it on paper for the cover of what is quite a prestigous magazine. Never before had an image of mine been used in such a fashion and, unsurprisingly, never since has it come to pass.

·

AS THE dust has settled and the tear gas has dispersed, a new parlour game has taken hold. People are vying to decide who won, and who lost, from the failure of the World Trade Organisation’s meeting in Seattle last weekend. Did the protestors, whether greens, trade unions or “anarchists” win? Did Bill Clinton, or Mike Moore (the head of the WTO), or big business lose? As the game is played (see article), one group, representing more than 5 billion of the world’s 6 billion people, sits bemused and befuddled, more or less ignored—just as in Seattle. These 5 billion live in the developing countries, and include the poorest of the world’s poor. They are the real losers from this whole sorry episode.

Those who wish to claim to have been the winners now also claim that last weekend marked the high point of globalisation in general and freer trade in particular. On this view, globalisation will now at least be halted, but preferably even be forced into reverse. The battle to prevent this from happening needs now to begin. But as that fight takes place, it is as well to be clear about who would stand to lose most if globalisation really were to be pushed sharply backwards—or, indeed, simply if further liberalisation fails to take place. It is the developing countries. In other words, the poor.

A tragedy of (mostly) good intentions

Few of the protestors think this way. Many seem to believe that they are on the poor’s side—against big, multinational conglomerates, against exploiters, against polluters. Even the trade unions, mainly American, who lobbied successfully to persuade President Clinton to press for labour standards to become more closely tied to trade, might well argue that their dearest wish is to help the Indian child whose picture is on our cover. They want to export America’s rules that protect workers against exploitation in various forms, including rules forbidding child labour. Nobly, just as they wish to spread democracy and human rights around the globe, so they wish to share their labour values with others.

Swallow, if you can, any scepticism about whether John Sweeney, head of the AFL-CIO union federation, really does have this aim in mind. Ask yourself, first of all, what the developing countries, gathered in Seattle, thought of this. They hated the idea. Partly, no doubt, because they don’t like things being foisted upon them. But also because they don’t think this is in their interests. In some cases, it might be right to dismiss that view: the interests of a government, and the elites that man it or control it, may well not be the same as the interests of a country’s citizens. But it is not right to dismiss it in all, or even most cases.

Think above all of India, home of our cover child. The world’s biggest democracy, for four decades it pursued policies of socialist anti-globalisation, shutting out trade and foreign investment as best it could. To put it mildly, this did its hundreds of millions of poor no good at all. Finally, in the past decade it has begun to embrace globalisation, gradually opening itself up to the world. Finally, its economic growth rate, and with it the welfare and prospects of the poor, has begun to pick up. The process has barely begun, but hopes are high. So India’s ministers troop off to Seattle to discuss further trade liberalisation. What are they told? By some, that they are making a big mistake to want to liberalise at all. By others, that they should do so only while imposing labour rules that make their factories less viable. Oh and by the way, the United States will not budge on its protection for textiles and on its use of anti-dumping laws, and the European Union wants to carry on keeping out foreign farm products.

The Indians could be forgiven for being disillusioned. They thought, after all, that they were trying to emulate the West. And what is surprising is that this has followed two years in which the world—for which read, the developing world—had passed a stiff test of its faith in open markets. The financial crash in East Asia in 1997 and the ensuing troubles in Eastern Europe and Latin America might well have begun a backlash against globalisation. Remarkably, it didn’t. The real question, it seems, is whether that backlash is going to begin in the rich, developed countries of North America and Western Europe.

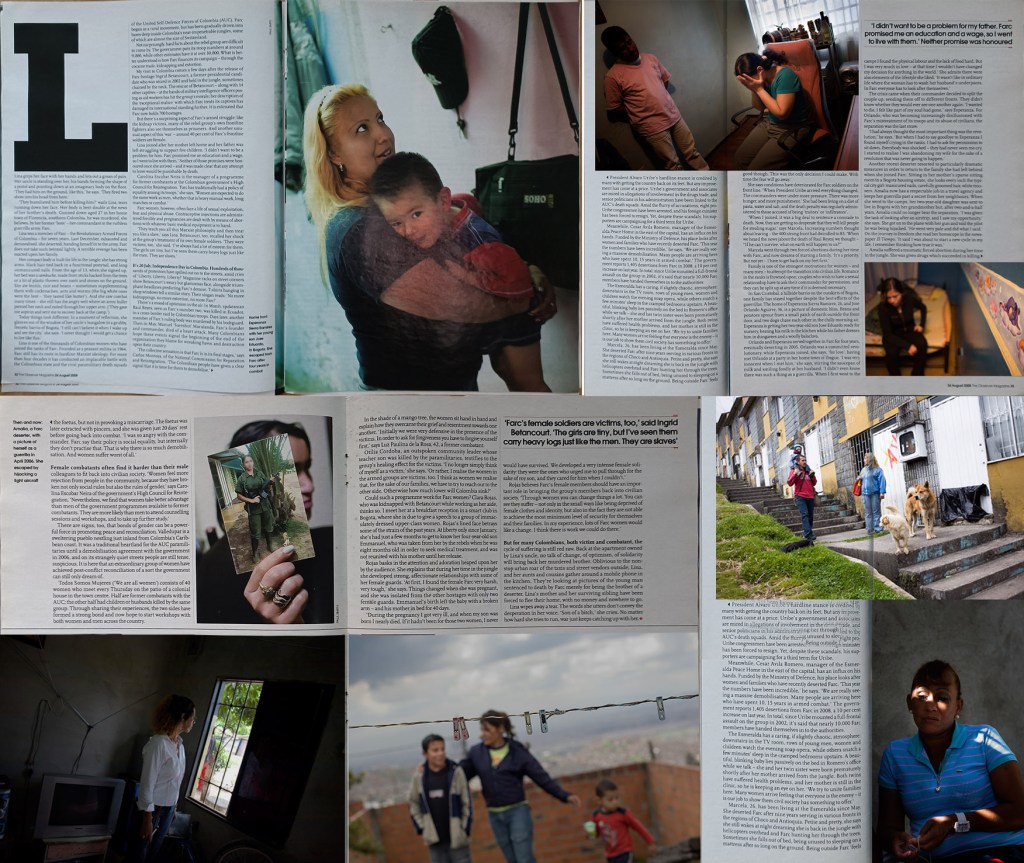

The Observer Magazine (London) · 2008

Revista Arcadia · 2006

Ford Foundation · 2004

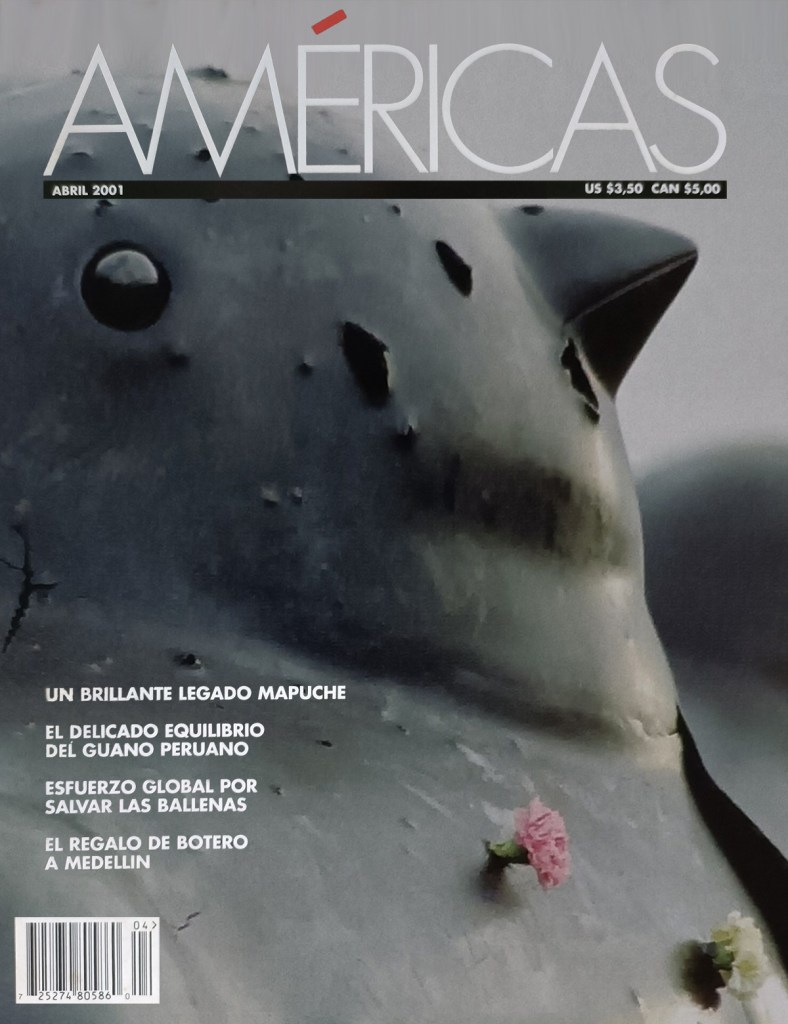

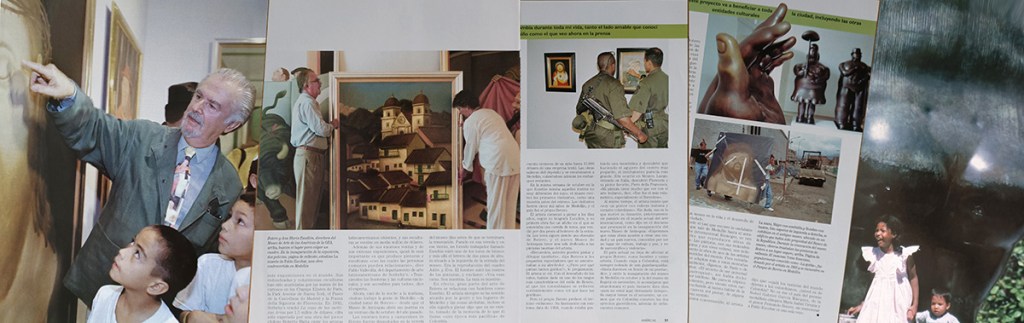

Revista Magazine · 2001

Fotos Für Die Pressfreiheit · 2011 – ISBN: 978-3-937683-33-1

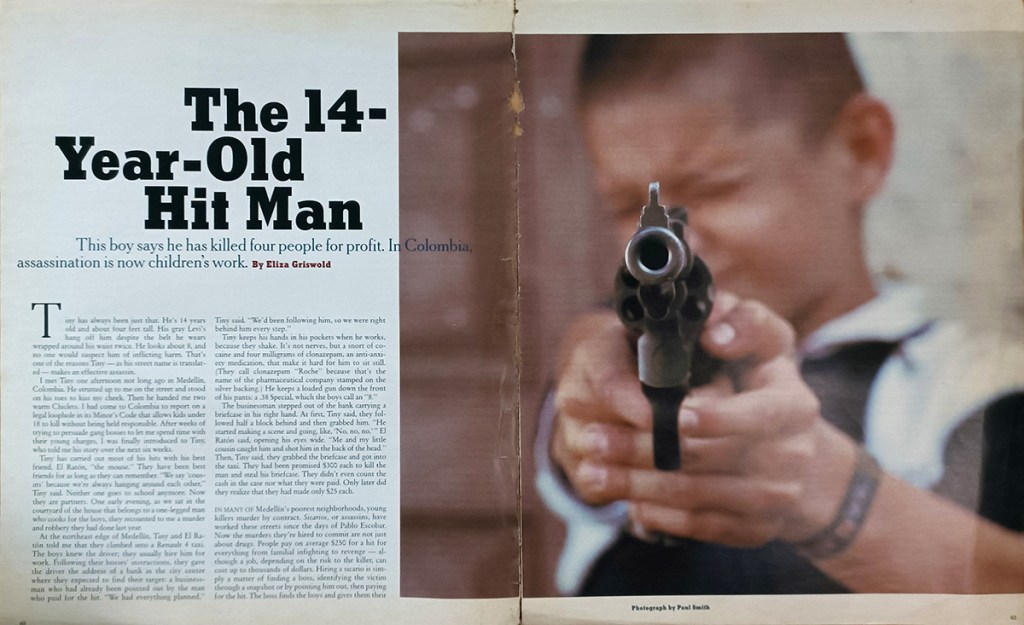

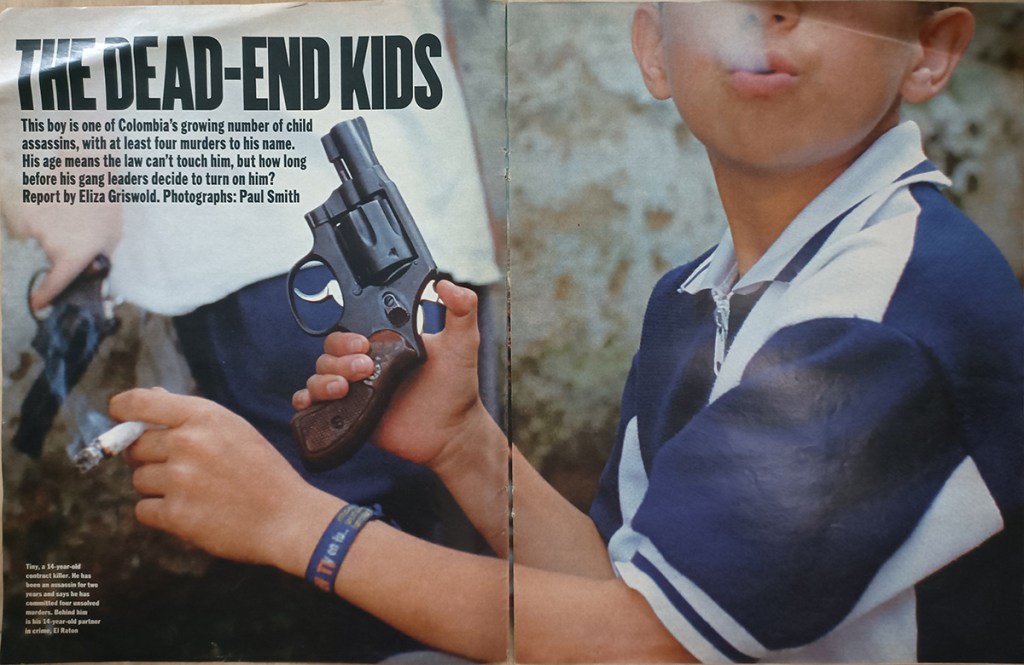

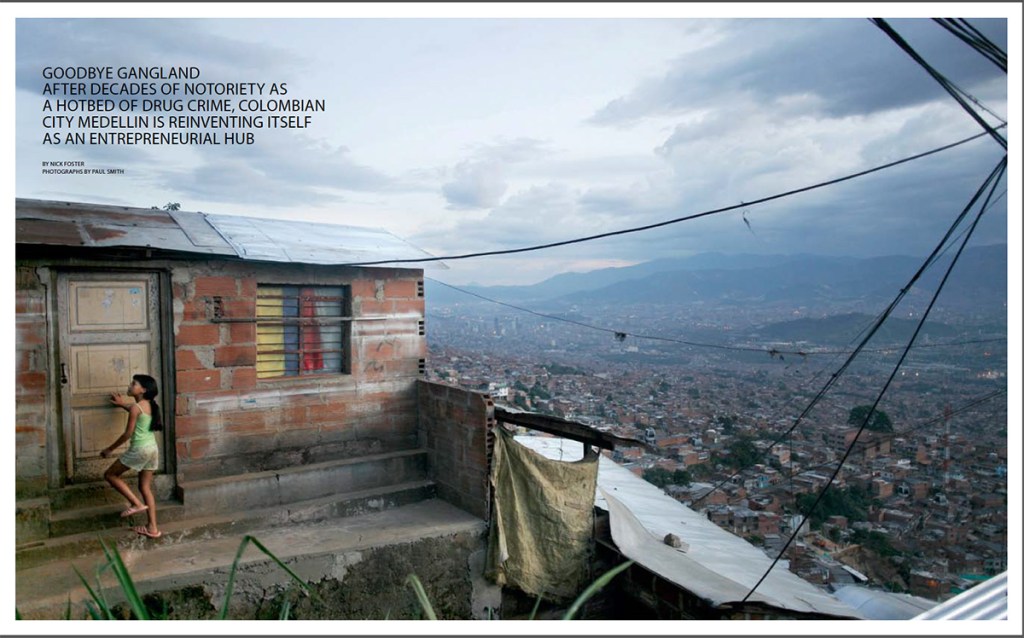

The New York Times Magazine · 2002 (Medellín, Colombia)

The Times (London) Magazine · 2003 (Medellín, Colombia)

The Guardian · 1997

Equity (Alemania) · 2013

Financial Times Wealth · 2014

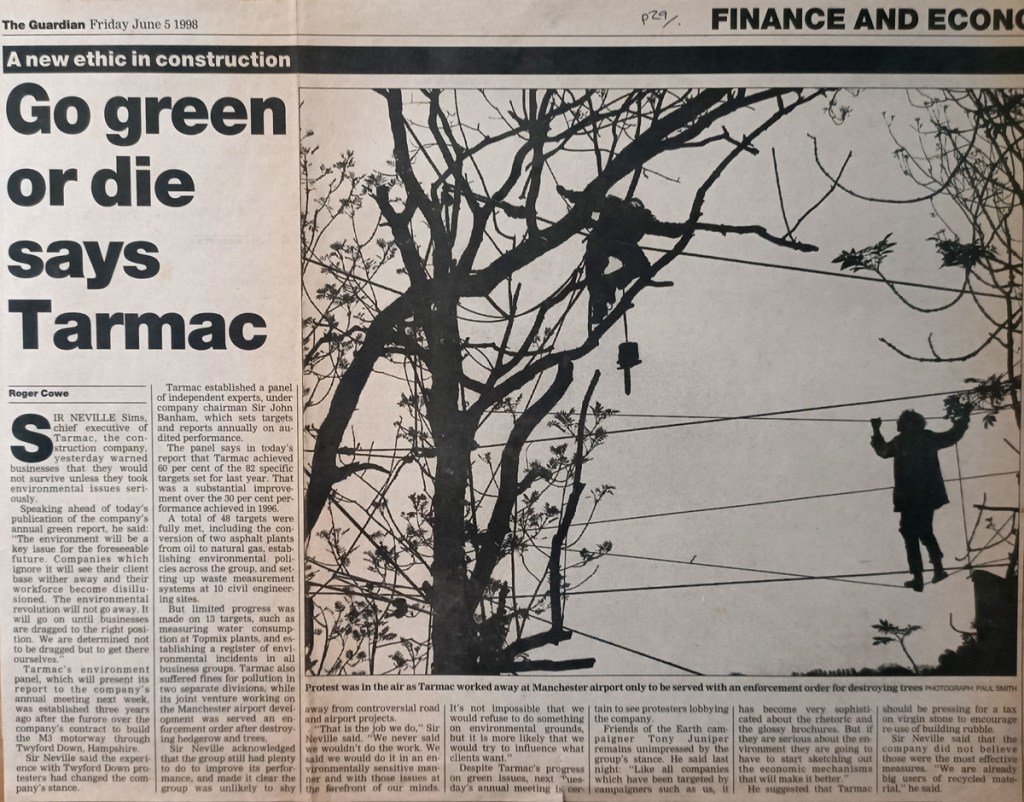

The Guardian · 1998

(Photo: Greater Manchester · 1997)

The Economist · 1998 (Photo: Edinburgh 1989)

Nicaragua · 1990

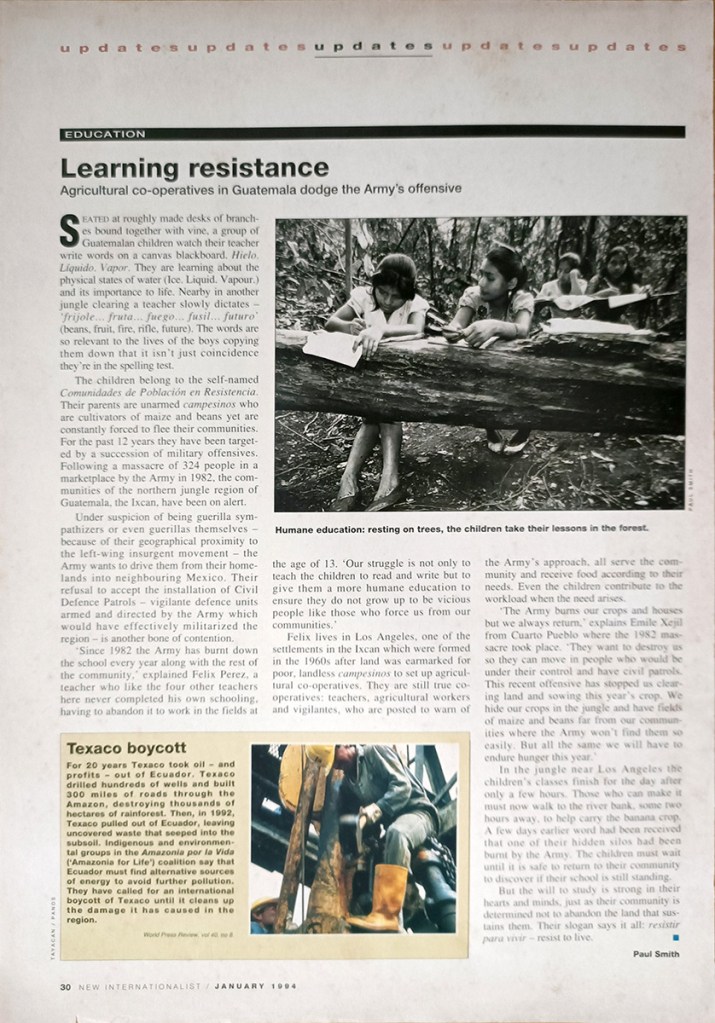

Guatemala · 1992

Comunidades de Población en Resistencia, Ixcán, Guatemala · 1993 (New Internationalist 1994)

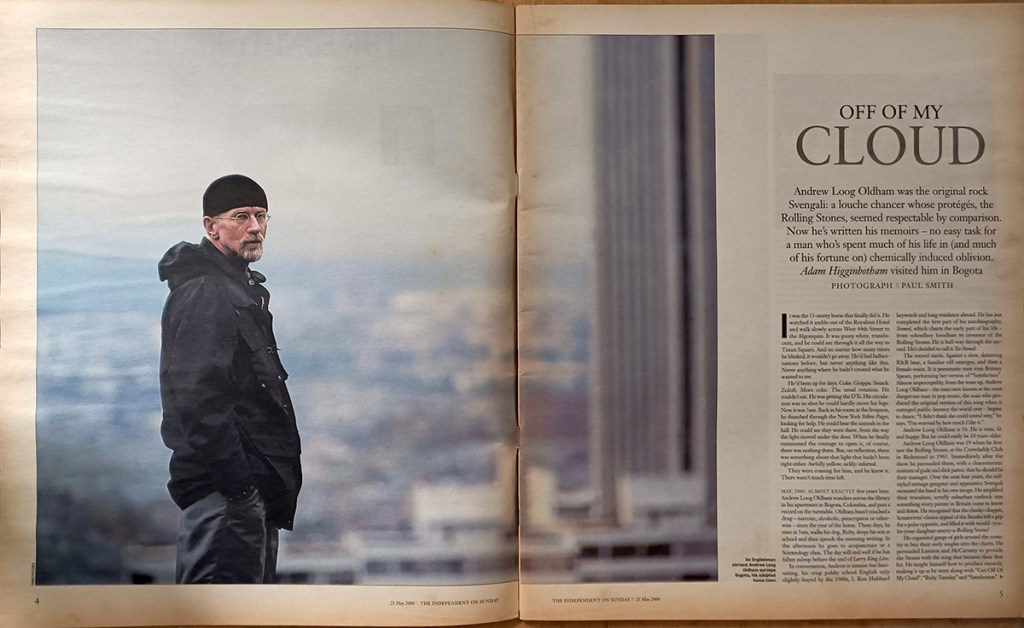

The Independent Sunday Magazine · 2000 (Andrew Loog Oldham – 1st manager of The Rolling Stones

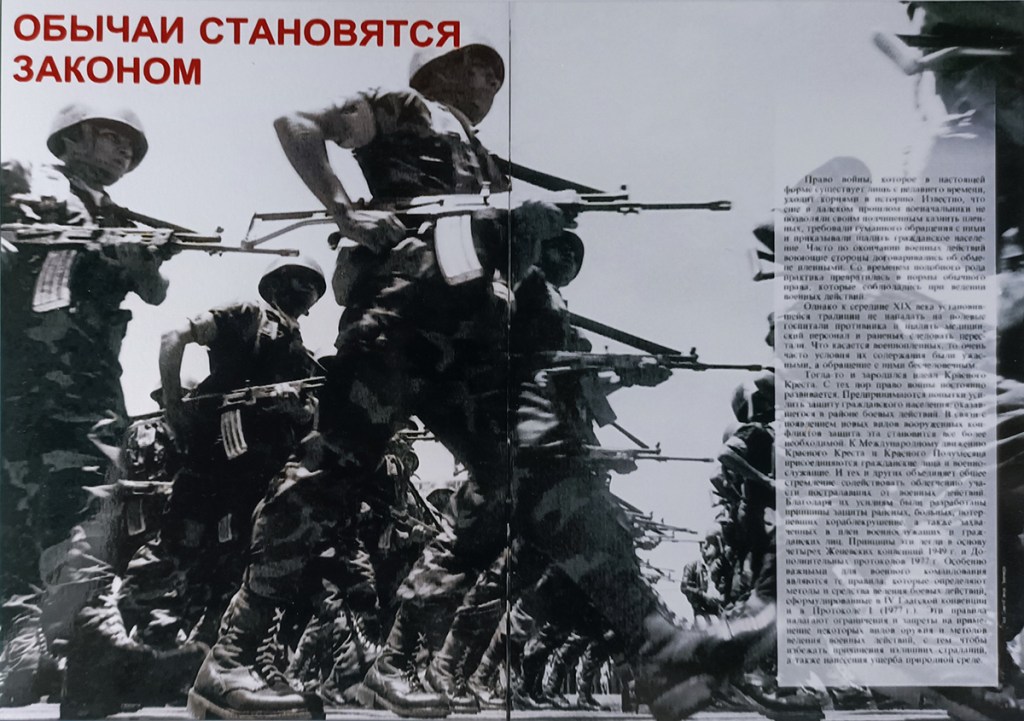

ICRC publication en Russian . 1995 (Above: United Kingdom · 1989) (Below: Guatemala · 1993)

Bogota · 1994

Bombay (India) · 1995

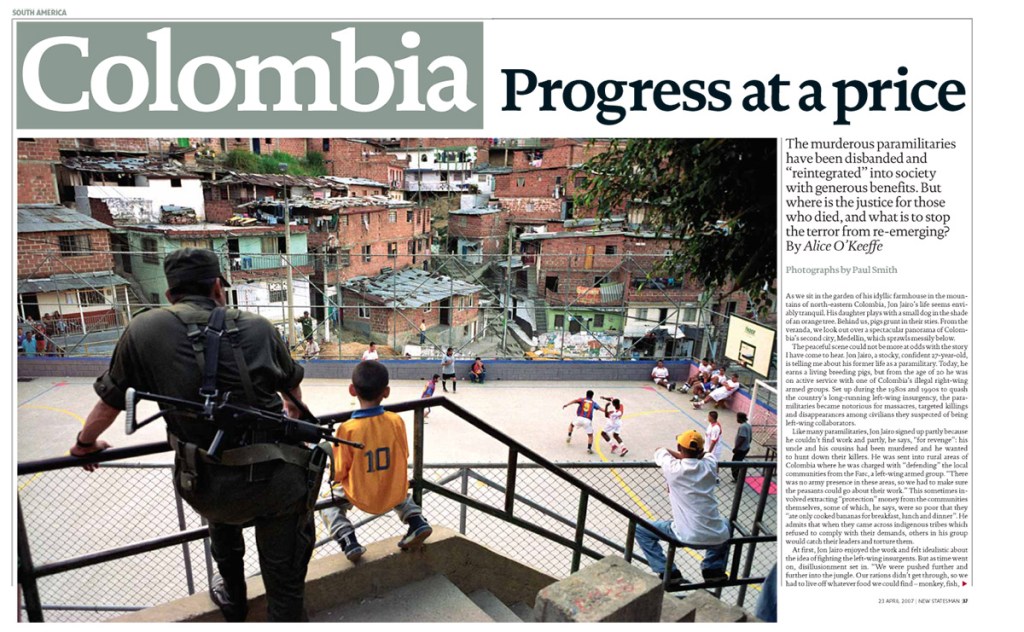

New Statesman · 2007

The Washington Post · 2010

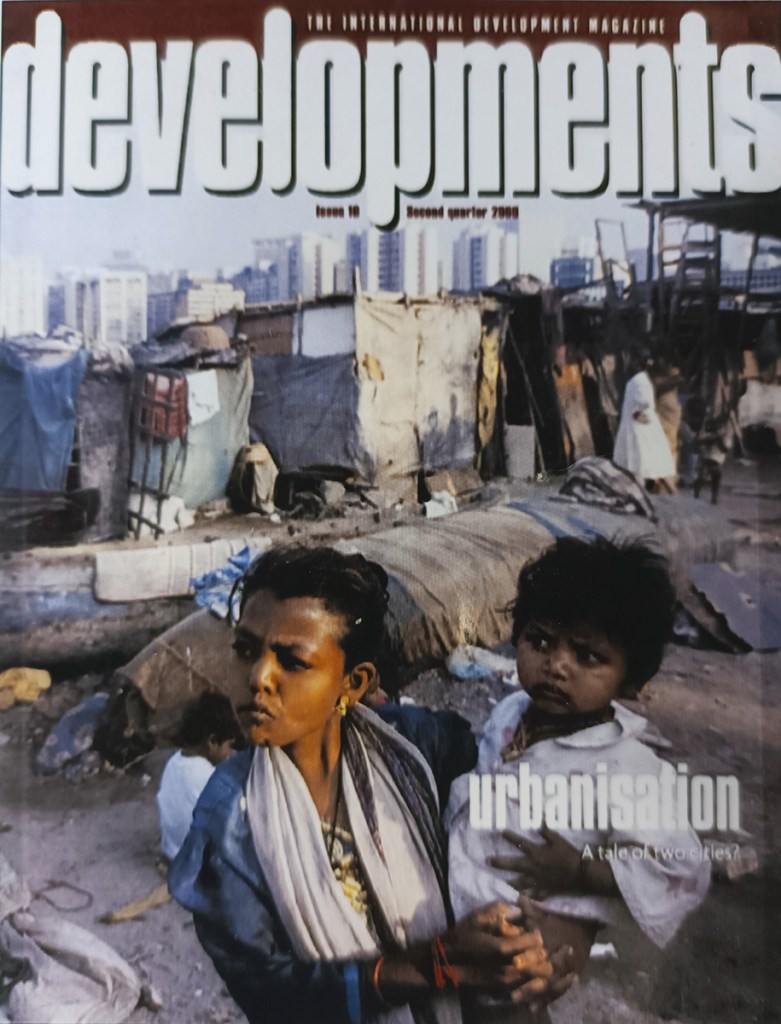

Department of International Development · UK (Photo: India, 1995)

The Financial Times ·

(Izq.) Revista Avianca 2014?

(Arriba) Revista Diners 2017

Geneva Declaration Secretariat – Small Arms Survey. Inclusive Cities · 2011

UNESCO – Sources · (Photo: Guatemala · 1991)

Fränkfurter Allegmeine Quarterly · 1997