Basic Training in the British Army

It was shortly after I had seen a documentary about the My Lai massacre1, perpetrated by troops of the US Army in 1968 during the Vietnam war, that I decided I would like to witness the process of training young men to be soldiers. I was in my first year at Newport School of Documentary Photography at the time and was mulling over what projects I would do for my finals the next year, so I wrote to the Ministry of Defence to pitch the idea that I wanted to photograph basic training as part of my studies. To my surprise, the MOD wrote back with a positive answer.

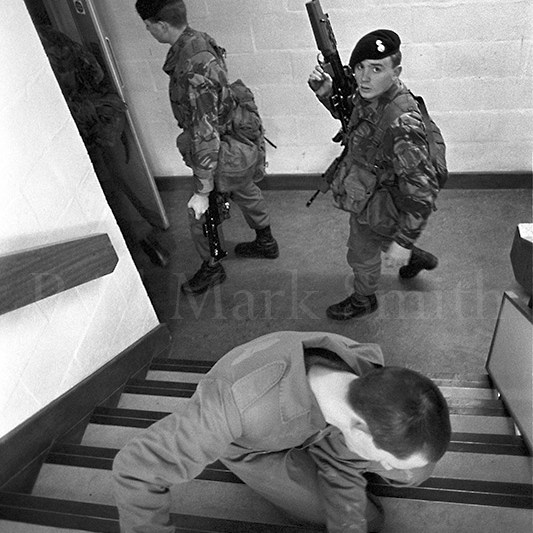

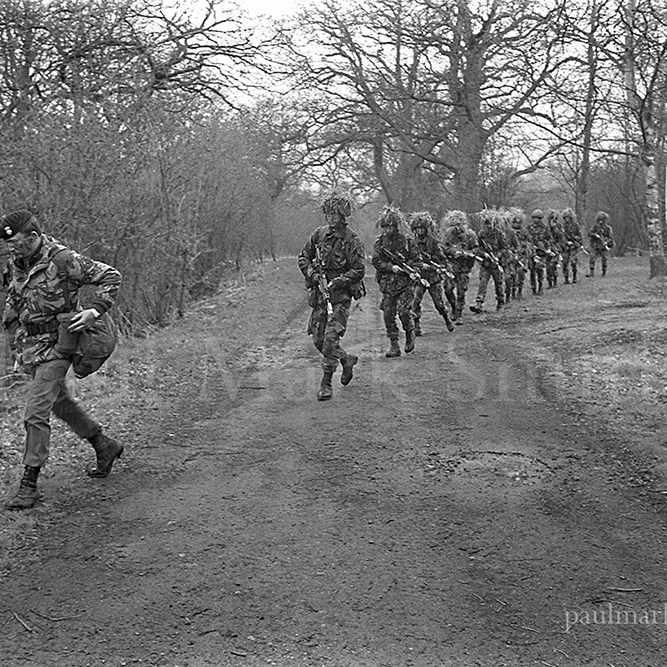

Regarding My Lai, my hypothesis that so many young men could not simply be evil. Hundreds of young soldiers and their officers had participated in the massacre of around 500 villagers – mostly women, children and aged men. There are multiple factors, I thought, that could contribute to the possibility of such war crimes being committed – among these, the killing of comrades by the enemy, fear, isolation and the military culture following and not questioning the orders of one’s superiors – but my interest was to be present and photograph the process during which young men would be regimented and bonded together through shared experience and a common cause.

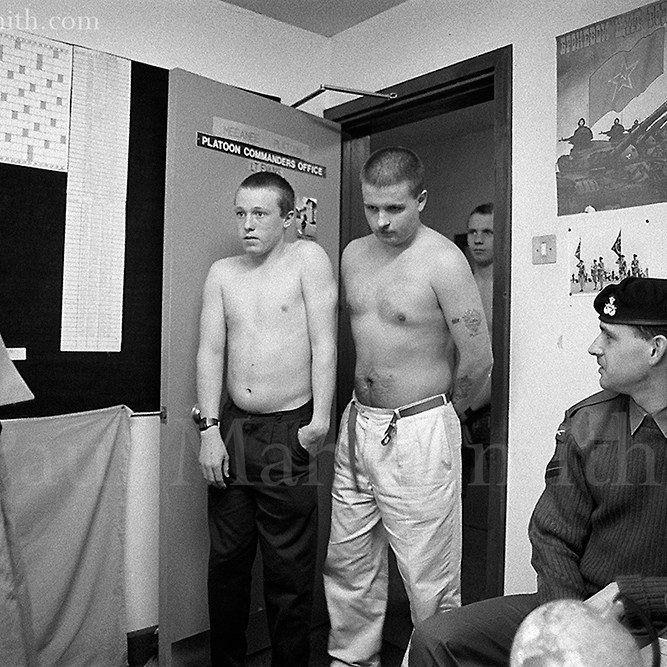

Alma Platoon. Day 1.

It was a dull autumn day of 1988 that I first met Alma Platoon. It was the same day that Alma Platoon met itself. One by one, twenty four young men from the Midlands and south-west of England arrived at the main guardhouse entrance of Litchfield Barracks with suitcases in hand. I spoke to many of them on that first day and began to get to know them, some better than others.

Gallery

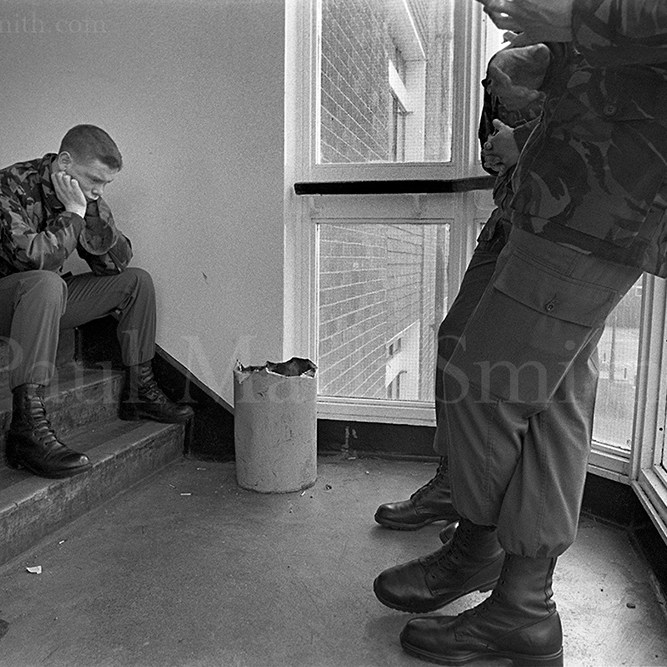

As the days went by, i could more or less understand their personalities and could see different dynamics emerge. The ribbing of some by others; little rivalries and hostilities between some towards others; the silent ones who would keep their heads down; the brooders; and the, apparently, clueless. Whether or not I was correct in my observations and assumption, there was really no way to be absolutely sure.

I was not embedded with them full time and I could not be sure that the dynamics would be the same when I was not present. I was in a somewhat privileged position in that I could hang out and chat with the new recruits, the NCO and, on occasions, dine and chat with the senior officers. I wore my regular clothes and did not don camouflage, other than when sleeping out during winter, as it was easier to buy kit from the quartermaster rather than go shopping for waterproofs. However, this privilege also set me apart – I could get along and chat with just about everyone and I never spoke of what I was told, saw or heard – but I was the one who was most different. I was not in the Army.

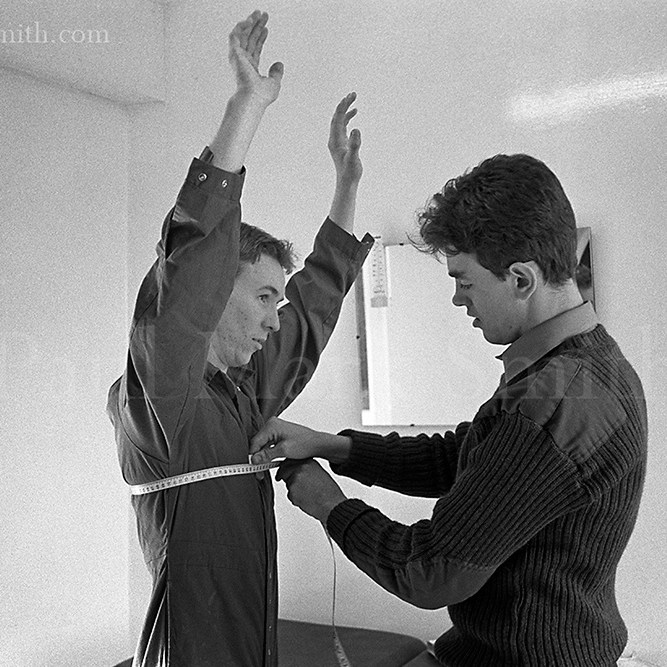

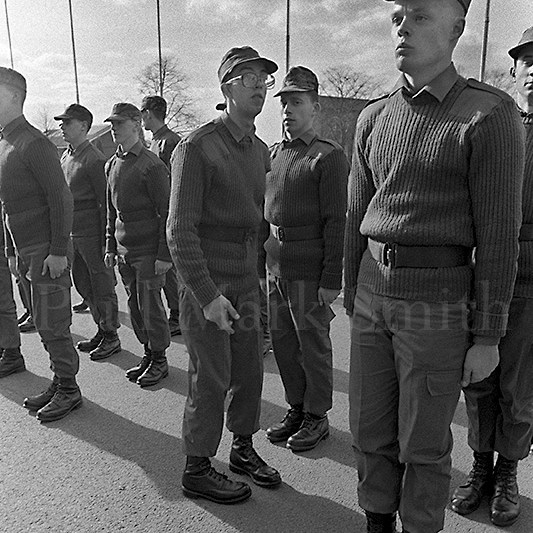

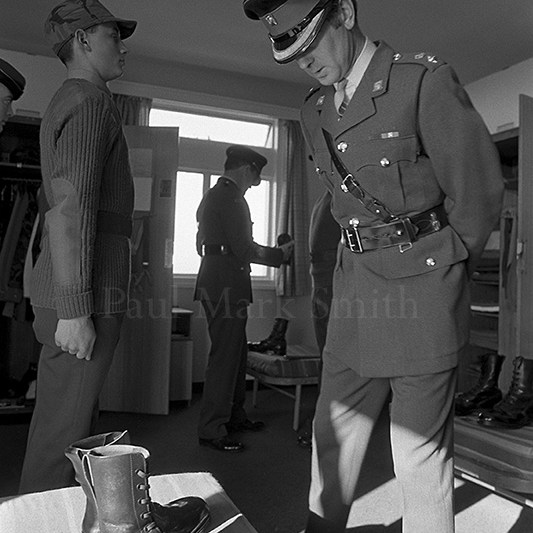

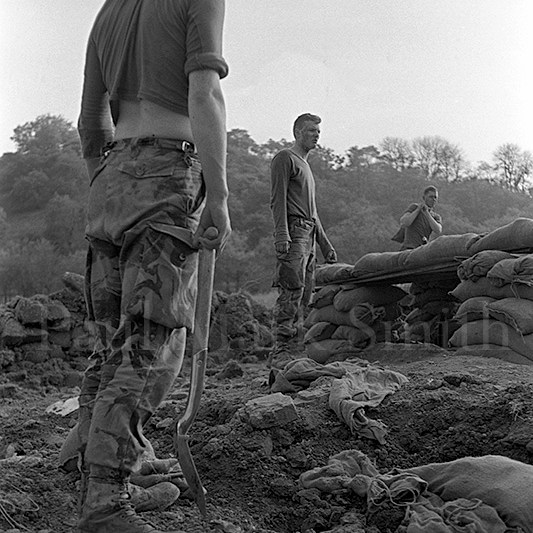

Much of the training revolved around getting the recruits to exert themselves and get physically fit. At the beginning, most of the lads were noticeably unfit, though there were several exceptions. Also, much of the training revolved around the repetition of tasks that had to be done exactly as stipulated by the NCOs. Tasks were repeated and repeated again until they were just as they were meant to done. The most obvious were activities such as marching, rifle drills, shining boots, and regulation presentation of folds and creases in the uniforms. But also folding blankets, laying out wash kits as required and cutting nails and cleaning ears . Gradually, Alma Platoon took shape and appeared to begin to act as a unit, though far from resembling the Grenadier Guards marching for the Queen.

Gradually, Alma Platoon was starting to act more in unison with each other and perform as was required. After four weeks, the lads were to be allowed to go out for a night out in nearby Litchfield. it would be the first time they had left the barracks since joining the Army. I can’t recall the last activities they were doing during the day before the outing. I was getting a little worn down by the repetition, was taking fewer and fewer pictures as a result and bid them farewell as they dressed up in their civilian clothes and sloshed on the aftershave. I drove back to my hometown, Northampton, and would catch up on events on Monday morning when I’d return to the barracks.

When I returned, I realised that I’d made a bad call. I should have stayed and gone out with the lads.

Film: Tri-X and Plus-X black and white negative. Cameras: Olympus OM-1 and Olympus OM-2

- The Massacre of My Lai – Vietnam 13 March 1968. US infantry C and B Companies of the 23rd Division of the US Army under the command of Captain Ernest Medina killed at least 347 and as many as 504 unarmed civilians, the majority of whom were women, children and aged men. Some of the victims, including children, were raped and their corpses mutilated. ↩︎