San Pacho

El Chocó’s Afro-Colombian Carnival

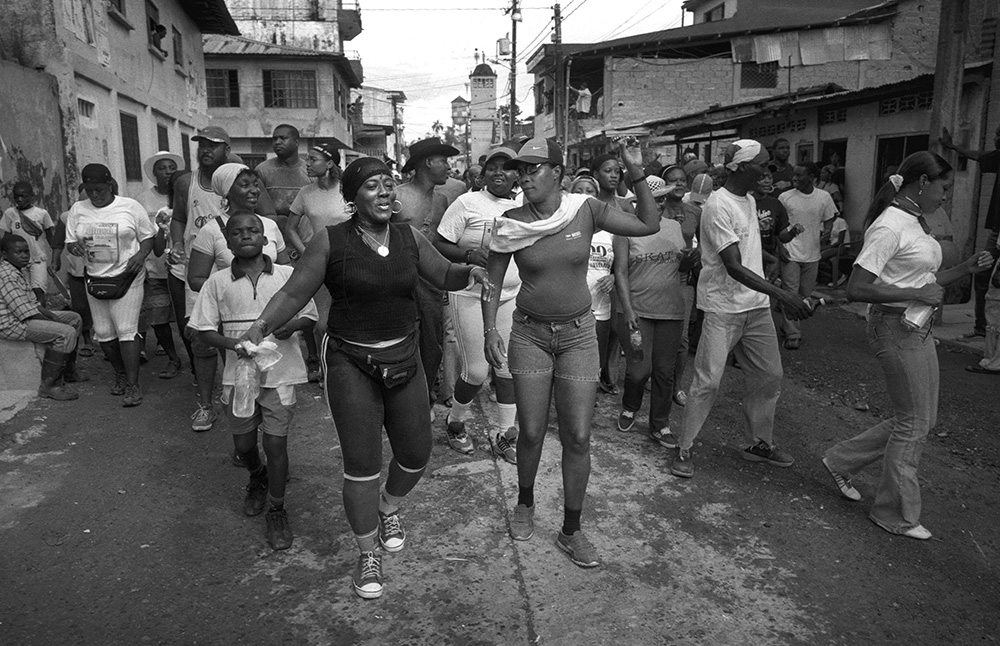

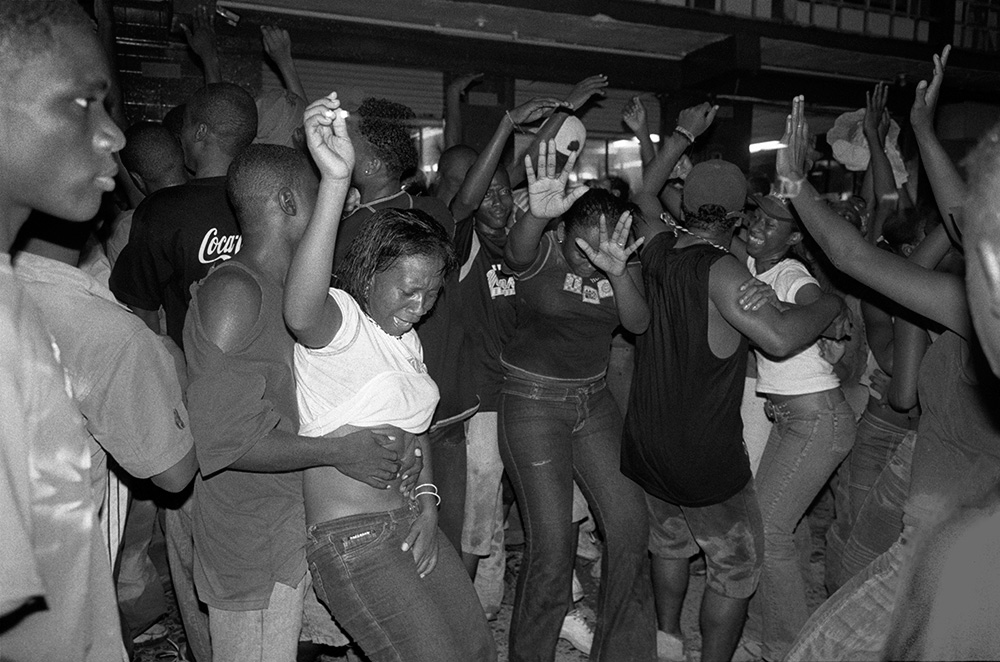

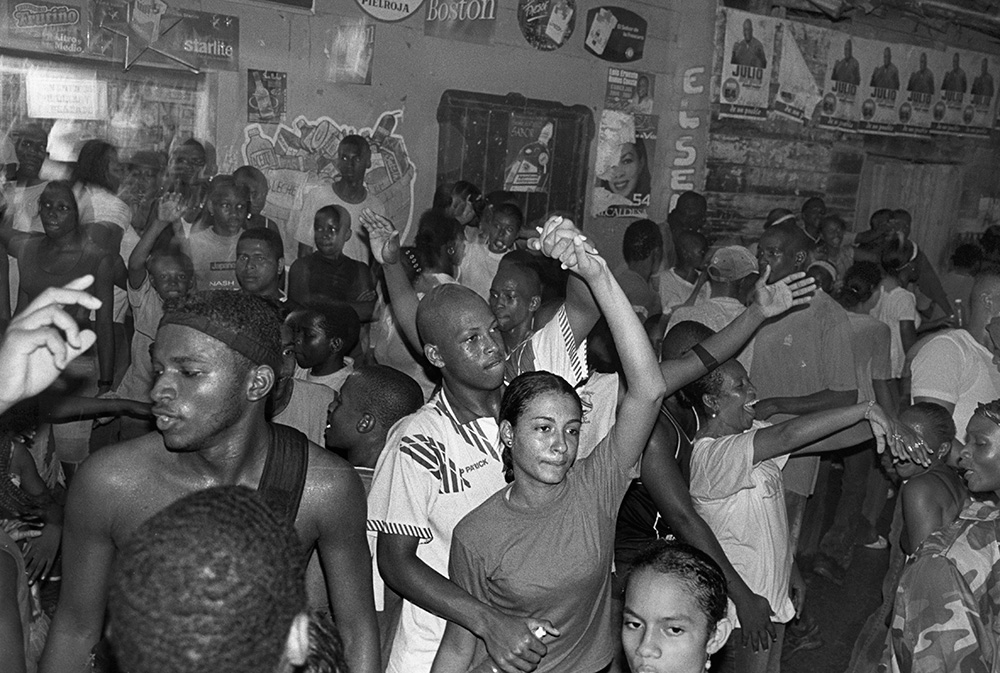

The predominantly Afro-Colombian city of Quibdó celebrates its annual Festival of San Pacho with Catholic masses, parades and carnival celebrations that honour the city’s patron saint, Saint Francis of Assisi. It is an energetic outpouring of music and dance rooted in religious and cultural syncretism of the African, indigenous and colonial heritage that form the foundations of city that is mired in poverty, yet rich in life.

all photographs © Paul Mark Smith

When The Saints Go Dancing In

For the European colonists, penetrating the interior of the hostile terrain of the New World continent very much depended upon encountering rivers and then sailing or punting upstream. In 1501, the Spanish conquistador Rodrigo de Bastidas came upon the mouth of the Magdalena River (then called Yuma by the indigenous tribes), which became the main conduit to explore and initiate the plunder of the Andean region of present day Colombia.

Likewise, in 1510 the Spanish explorer Alonso de Ojeda came upon the mouth of the Atrato River and opened up what is present day Chocó to exploitation and colonisation. The Pacific region was hot and inhospitable, so didn’t attract many colonists. It was covered in impenetrable tropical forest and one of the wettest places on earth and covered by a vast network of streams and rivers that deposited substantial amounts of alluvial gold, which brought many miners who were willing to endure harsh conditions, particularly when others could be enslaved to do the hard work of extraction.

Saint Francis of Assisi Cathedral

Initially, the colonist miners enslaved the indigenous people to work in their mines, breaking their spirits and bodies and working them to death, whilst Catholic missionaries set about saving their souls by converting the native peoples to Catholicism. The next life would offer better opportunities than their earthly existences. As indigenous beliefs merged with the Catholic faith, their populations were decimated.

Quibdó, the capital of el Chocó, was founded by a miner turned Franciscan priest, Fray Matías Abad, in 1648. Around this time, the first shipments of African slaves had begun to appear in the jungle region. They were considered hardier and more durable beasts of burden than the indigenous population. Quickly and markedly the demographics changed considerably. Quibdó, restocked with African slaves, would be a majority afro-colombian settlement/city. Its founder would not see how the settlement would develop: a year later, as he travelled down the River Atrato towards the Caribbean Coast, he was killed by Kuna natives. The Kuna, unlike the Choco and Emberá indigenous peoples, did not regard the white Europeans kindly – indifferent to whether they be missionaries or miners.

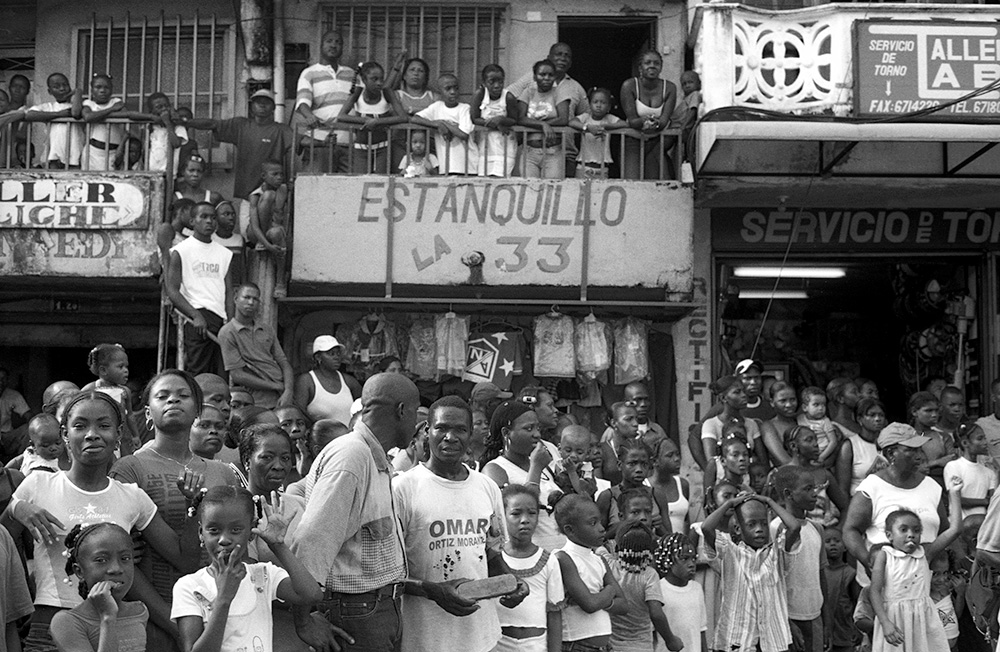

The festivities last for a month or more, as the party moves around the small city’s barrios (neighbourhoods). On the last Sunday, a Catholic mass is held in the morning, after which secondary school martial bands parade with religious paraphernalia.

As the boats brought in new shipments of African slaves, a steady trickle of them self-emancipated and slipped away into the jungles to settle far from their European slavers. In 1851, slavery was officially terminated in Colombia, by which time, after more than a Century of importing slaves, the province had a predominantly Afro-Colombian population.

The dancing throngs during the festival are known as the “Bunde”, which is a traditional dance of the Emberá Katio indigenous people that evolved after being adopted and adapted by the afro population that had fled to regions inhabited by natives, far from the European colonist slavers.

Small-scale mining continued but many of the European miners left, as they could no longer count on having human chattels, which made the business less profitable. When steamboats began to ply the waters of the Atrato in the mid-19th Century, the region became more accessible and mining picked up and continued for much of the 20th Century until the steamboats stopped and, again, most of the foreign miners left. The province slipped into pleasant abandon, becoming a forgotten corner of Colombia, beyond the frontiers and abuses of colonisation and the violent political conflicts in the rest of the country.

The festival of San Pacho has been celebrated on and around the saint’s day for more than 300 years but only since 1926 have parades and costumes been a feature.

The region was pretty much left alone, other than the gradual plunder of its natural resources by companies from the neighbouring provinces that were settled by the white skinned colonists. The extraction of these resources was more often than not done by locals and sold to the buyers at shipping hubs, such as Quibdó … Gold continued to be mined, timber extraction was very profitable and became rampant. As local community leaders began to oppose the deforestation, pressure came to bear upon them from paramilitary forces allied with the big businesses and also the Army.

In 1997, after years of abandon, the Colombian State made a major investment in el Chocó. Unfortunately, this investment was in bombs and bullets and Operation Genesis, which heralded a new era for the province. Spearheaded by the Army and right-wing paramilitaries, the forgotten region became synonymous with the armed conflict in Colombia – its principal victims the afro-colombian population that occupied strategic land with abundant natural resources and a rich biodiversity.

See “Genesis – the beginning of the end”

In recent years, commercial interests and advertising have crept into the parades. Where before there was only flamboyant carnival costumed dance troupes, now stores mix in groups of people wearing t-shirts and ponchos with the logos of businesses and even football fans of teams in neighbouring departments – but not el Chocó – participate.

On the banks of the Atrato River, children pose before a backdrop of an Antioquian landscape. The photographer, Wilson, is from the neighbouring mountainous Department of Antioquia. He told me that the landscape was very popular and that the locals preferred it to the flat horizon of the Atrato River on whose shores he worked.

Another curiosity was the presence of youths parading in military fatigues with weapons made of wood and tubes of guadua. The armed conflict had hit hard in the Department of el Chocó. Every time I had previously been in Quibdó it had been related with the conflict: reporting on paramilitary repression of community leaders and mass, forced displacements of communities; on displaced communities in the city’s periphery; shorty after Bojaya massacre, when the airport buzzed with helicopters and soldiers and the quayside with the waves of displaced people fleeing the bombardments. They reminded me of paramilitaries, who I had photographed in their training camps, where new recruits marched, did press ups and ran around with wooden rifles.

The girls carried more realistic looking weapons. As they bobbed and wriggled along with the parade with their silver 9mm pistols, they drew many a look from men assembled on the fringes. I even saw a kid brandishing one of these pistols in the airport and waving it in people’s faces. Unthinkable that such could happen in a post 9-11 airport, but nobody batted an eyelid!

Colombians, like many other parts of the globe, consume mountains of plastic shaped into an infinite number of shapes or woven (as nylon) into brightly coloured clothes that will fall to pieces in months if not weeks. They flow into the country, more often than not from Asia, in metal shipping containers and many finish their ephemeral existence loose and abandoned, flowing down the abundant Atrato river and on into the Caribbean to litter beaches and choke turtles and seabirds to death.

Footnote: Many years have passed since I photographed the festivities of San Pacho in Quibdó. The region was still embroiled in the armed conflict, which had abated a little since the the late 1990s and early 2000s with the authoritarian paramilitary control having firmly rooted themselves in the Lower and Middle Atrato. The festivals itself was still authentic in nature and roots, but commercialism was beginning to filter into the parades and the other festivities, as it has done so in other colombian festivities. Paul Mark Smith · Medellín, Colombia 2025

Anecdotal Information